by Nicole Yurcaba

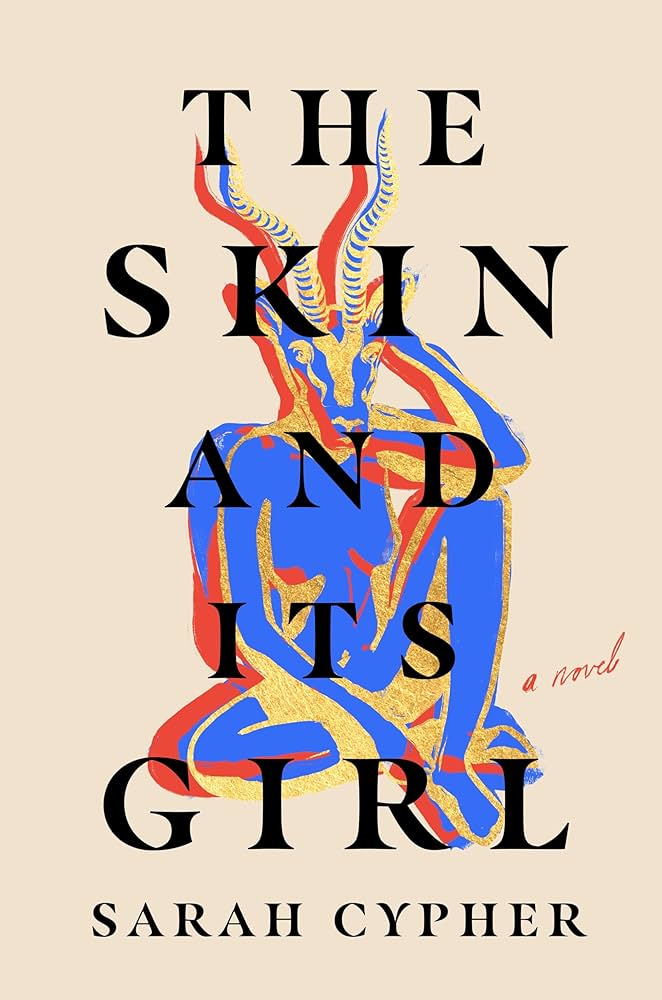

Sarah Cypher’s The Skin and Its Girl is one of those novels that I quickly gravitated toward after the Hamas-Israel events of 7 October 2023 began. The Skin and Its Girl is a refreshing read during an incredibly dark time. The main character, Betty Rummani, is a new kind of heroine, one that challenges ableist narratives, and the secondary character, Aunt Nuha—keeper of family lore and family matriarch—is a feminist in her own right. Thus, The Skin and Its Girl stitches together an older generation’s story with the younger one’s to create a story of personal resilience, queer love, and the generational consequences of being forced from one’s homeland.

One of the most powerful attributes about The Skin and Its Girl is how it offers a bit of something for everyone. If one’s looking for a new kind of heroine, then one finds that in Betty. For example, Betty is the type of character who, from her beginning, defies traditional social and cultural narratives. Doctors, at first, think she is stillborn. However, as her heart begins to beat, her skin turns cobalt blue. Aunt Nuha attributes Betty’s blueness to the family’s sacred history and recollects a time when the Rummanis were among the wealthiest soap-makers and their blue soap symbolized legendary love. As she journeys through childhood and adulthood, Betty endures taunting and bullying not only because of her blueness, but also because of her large size. Even though her mother tries to protect her from the world, Aunt Nuha and Betty’s semi-estranged father convince Betty’s mother to allow Betty to begin school and actually living. Betty endures the bullying, for the most part, with grace and maturity, but the deep loneliness that permeates her existence is undeniable. In her adulthood, as Betty stands at Aunt Nuha’s gravestone trying to make a life-changing decision, Betty cycles through various scenarios and family histories as she talks through her own sexuality, life circumstances, and familial binds with Aunt Nuha. It is Betty’s forethought and kindness, too, that will inspire others. Unlike many of the novel’s characters, Betty constantly reminds herself that her actions, her decisions, and her words affect others.

The Skin and Its Girl could be considered a novel about self-love, or rather, the journey to finding self-love and how one’s exile can lead to the discovery of self-love. As Betty faces social conflicts because of her blueness as well as her family’s Palestinian American identity, readers see her struggle with self-esteem as well as her place within society. At one point, she reflects, “When there is no other beginning but the broken middle of things, we find ourselves in a kind of limbo, in empty towers, following branching hallways, whispering to the walls. Searching for a chance to find others, to build sense out of similarity and affiliation.” It is at such points that readers see why Betty and Aunt Nuha developed such a closeness. Due to her own exile and immigrant status, in the United States, Aunt Nuha faced seemingly insurmountable discrimination and ostracization. Of course, Aunt Nuha has a different self-preservation approach than Betty—humor. Aunt Nuha’s wit often blindsides others, and because of her utilization of this tactic, many in the book see her as obnoxious and belligerent. In Aunt Nuha, readers see a fully developed character whose confidence and boldness has formed from the very socio-political and familial conflicts she has endured for decades.

At one point, Betty asserts, “What unites us, besides the universal word for human, is our tendency to universally ignore warnings when our nature pulls us toward what feels right—or at least toward something that feels better than the truth.” Essentially, each and every page of The Skin and Its Girl is a tug towards truth, both universal and personal. This book pairs well with Zeyn Joukhadar’s The Thirty Names of Night, and both Betty Rummani and Aunt Nuha have positive lessons about survival and self-love to teach anyone who’s willing to read their stories.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post