by Nicole Yurcaba

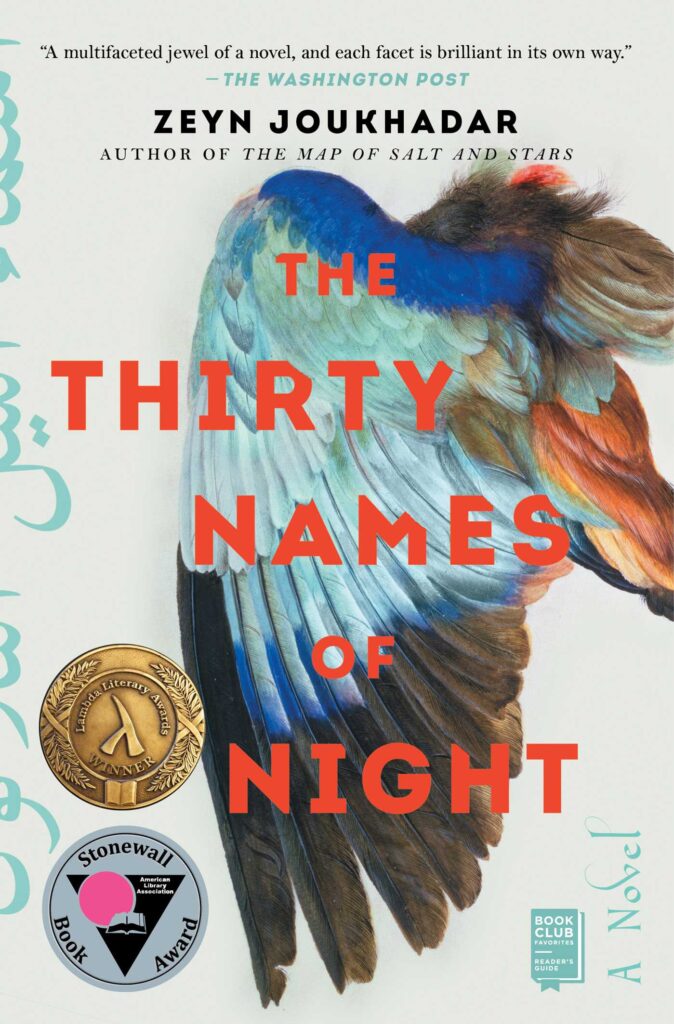

In Zeyn Joukhadar’s The Thirty Names of Night, readers meet a closeted trans boy whose mother died in a suspicious fire. While the circumstances surrounding his mother’s death and the consequences of that fire are integral to the novel’s plot, what really drives the novel is the boy’s search for something even more meaningful—an immigration legacy which has shaped his present circumstances as well as the pursuit of a new name as he sheds his birth moniker and birth identity. However, when the boy discovers the journal of Laila Z, an artist who disappeared decades ago, the boy discovers stories and histories of queers and transgenders within his own community that he did not know existed. Evocative and poetically written, The Thirty Names of Night is a gorgeously told story about the power art, the necessity of honoring one’s heritage, the quiet ways in which one protects the environment, and the steps one takes to find a place in which they belong.

The Thirty Names of Night is one of those novels that is so sweeping, one will start reading and forget that two hours ago they were supposed to go to bed, place the laundry in the dryer, or go to work. The language in the novel is poetic, magical, and philosophical enough without being daunting or overwhelming. As one reads, they encounter passages like, “Tomorrow, when the ghost of you enters my window with the smell of rain, I will tell you how, since you died, the birds have never left me.” Ghostly and haunting, such passages reinforce not only the personal, but also the generational, loss experienced by many in various immigrant communities as communities change and older generations die. However, the poetic language, too, creates a sense of personal accountability for one’s actions, words, and responsibilities to which one must remain true: “If we live, it’s only because some distant galaxy lent us its dust for a while. Ghosts are more honest than the rest of us: they can’t help but be what they are.” Thus, other passages are more sensitive to the individual’s smallness within the context of society or, more philosophically, the universe. They are also a testament to the engrained legacies that one may carry due to cultural expectations, generational traumas, and heritage.

The Thirty Names of Night also addresses the more difficult issues facing immigrants, immigrant communities, and the LGBTQ community in America. The book definitely does not shy away from addressing these issues, and it frequently acknowledges the racism, discrimination, and violence experienced by the Arab American community. The boy’s own mother was a victim of such violence after opposing the city’s demolition of Little Syria. The novel also portrays instances of Syrian businesses being attacked by having their windows smashed and the businessowners sustaining injuries. These portrayals resonate with the recent surge in violence against Muslims and Arab Americans during late 2023. Amid the violence, however, the boy offers wise insights that, if heeded, would result in a better society overall: “How different the world would look if it had any mercy toward migrations undertaken as a last resort against annihilation.”

One cannot read The Thirty Names of Night without recognizing that the novel is an eco-urban manifesto about honoring and protecting the environment, primarily through art. Birds hold a revered place in the novel, and they also influence the boy’s mother’s career as well as Laila Z’s art. The birds’ migration patterns, too, are important to the novel’s messaging about the significance of migrating place to place and the importance of respecting and preserving such settings. Readers might even infer that the bird sanctuary operated by a friend of the boy’s family and its demise are symbolic of Little Syria and, therefore, serve as a type of foreshadowing.

Of course, readers will also make note of The Thirty Names of Night’s discussion regarding self-acceptance among members of the LGBTQ community. Frequently, the boy hints at never being able to fit into a “sisterhood.” The boy also details the physical turmoil of dealing with his body’s rejection of an IUD. This clues readers into the fact that the boy is transitioning from being female-assigned-at-birth to male-identifying. Readers also see the boy working toward social transitioning as they acknowledge spending “so many years feeling alone, not knowing to ask the right questions” and “denying” their true self. Paralleling the boy’s journey toward self-acceptance is the boy’s discovery of a painting of a rare bird by Laila Z, a painting many claimed Laila never finished. As he searches for the painting, he meets characters like Sami and Qamar who have embraced their own queerness. Therefore, the novel transforms into a bildungsroman of sorts, especially as the boy sheds his old self and embraces the new one.

The Thirty Names of Night is bold and stirring, evocative and unforgettable. The emotional, physical, and historical paths readers wander while in its pages will be paths they’ll have difficulty leaving—even long after they’ve closed this book.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post