by Nicole Yurcaba

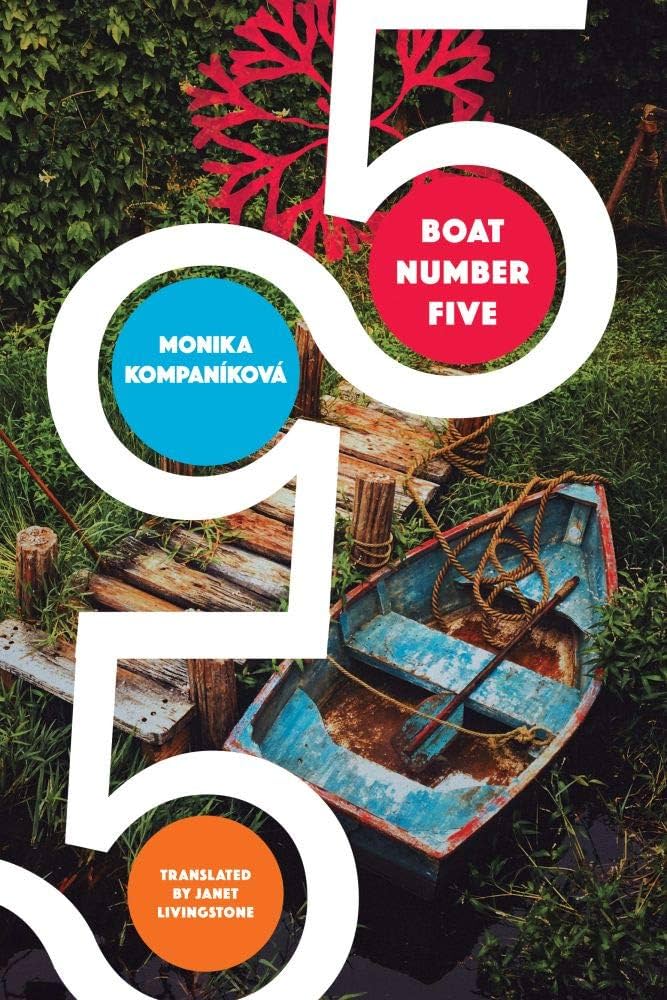

As a Ukrainian American, I have a special place in my vyshyvanka heart for Eastern European literature. Thus, for Sage Reviews, I’ve chosen Monika Kompanikova’s book Boat Number Five to open April’s schedule. Published by Seagull Books, Boat Number Five might best be described as a Slovak version of Lord of the Flies. Neglected by her partying, promiscuous mother, twelve-year-old Jarka becomes the caretaker for her immediately dislikeable grandmother, Irena. One day at the train station, a distressed mother leaves her twin babies with Jarka, and Jarka and the twins embark on what Jarka believes will be a life of independence and happiness by living in an abandoned garden hut where no adults will find them. However, even though Jarka firmly believes that her days of taking care of Irena have adeptly prepared her for nursing twins, Jarka’s life and happiness with the twins quickly disintegrates into domestic madness.

Boat Number Five is gritty and real, a social commentary about post-Soviet Bratislava where crumbling housing complexes create social vacuums for children left to their own devices as their parents navigate new means of survival. Neglect is a paramount theme in the novel, and while Jarka’s story is the novel’s essential focus, readers see others living in neglectful, concerning situations. Most memorable is the set of twins who, on a daily basis, venture to the local bar to guide their drunk parents home and to safety. Juxtaposing both Jarka and the others is Christian, a seven-year-old only child whose parents are wealthy enough to buy him nice clothes, make sure he is properly fed, and provide for him a relatively sheltered life. Nonetheless, influenced by a few of the brutal, bullying boys who scour the housing complex seeking their next victim, Christian makes the decision to steal money from his father and run away from home after the boys threaten Christian. Christian’s decision leads him to Jarka and the twins, where–away from the comforts his parents provide–Christian devolves into a new creature, one slightly reminiscent of Piggy in Lord of the Flies.

The chaotic, inattentive homelife Jarka experiences is what readers initially enter. Jarka comments that her family is a “family operating on the principle of barter” and that nothing “good ever came of these little business deals.” It is an interesting observation for a twelve-year-old to make, but it can also serve as a quiet stab at Slovakia’s fair share of corruption during its post-Soviet years. Readers also see how the Soviet system ultimately perpetuated an apathetic environment and state-of-mind since individuals were stripped of their individuality and free will. This is most evident in Lucia, Jarka’s mother, who at one point tells Jarka, “You don’t have to take responsibility for both the small and big decisions always and everywhere, you can let it go and just watch.” Lucia also asserts, “It’s nice to not think too much. It’s easy to let yourself be led by chance, to copy the direction of the wind, the path of a flying piece of paper or a stray dog.” Thus, what Kompanikova proficiently depicts, nonetheless, is the maddening state–both literal and figurative–in which Jarka lives.

Boat Number Five, too, serves as a commentary on the generational augmenting of violence. While that is superficially evident in Lucia and Jarka’s existence, it is also evident in how Kompanikova portrays Bratislava. It reveals itself even more as the novel progresses and Jarka develops as a character. Even though she is technically a child, Jarka does not see herself as one. She frequently places herself in opposition to the other children she encounters. At times, Jarka conveys this opposition with a precocious tone, especially when she makes observations such as “Children are small and live too close to the earth, and much good remains in them from this.” She also asserts, “No one can stuff their own truth, wishes or failures into children, because they’ll rip apart and all the betrayals will tumble out at once.” The system of violence and abuse becomes even more apparent when, years after the incident involving the twins, Jarka’s mother tells Jarka that Jarka was “responsible for everything bad,” which leads Jarka to believe that she is responsible. She lives in an effort to “not let anyone get so close enough for me to hurt them unintentionally,” which, in some ways, might be Jarka’s attempt to break the cycle of violence.

Thus, Boat Number Five is a book entirely its own, a psychological and socio-political thriller that’s a masterpiece in its own literary right. At times philosophical, at others introspective and poetic, in Baudelarian fashion it dissects life’s grittiness and ugly parts at which some would rather not look. At its end, however, readers realize it’s a study of human relationships and of the aches and wounds which never seem to heal.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post