by Nicole Yurcaba

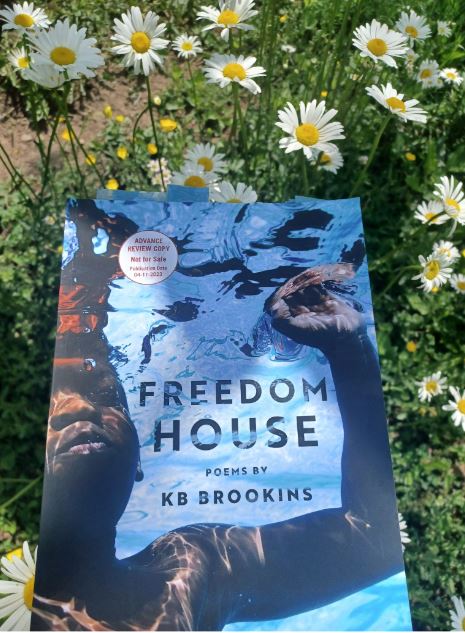

There’s nothing quite like a poetry collection that arrives and spits in the face of illogical and ideological agendas like Florida governor Ron DeSantis’s latest contribution to anti-LGBTQ

laws sweeping the United States. While KB Brookins’ Freedom House is not a Floridian collection, its manifestations of social injustice and political inequalities take a swing at another state which frequently makes headlines for its anti-LGBTQ, racist policies – Texas. However, as politically and socially focused and nuanced as it is, Freedom House is an exploration of the self. Its speaker is confident, bold, and blunt, and the collection stands as a beacon to those in marginalized communities needing inspiration to find their voices.

“KB’s Origin Story” is rife with a deprecating tone. The speaker describes themself as being “born a weary son.” Readers sense the speaker’s disconnect with their family as they admit “I can’t / fit in.” Phrases like “I pain myself” repeat throughout the poem, and the repetition reinforces the speaker’s attempts to continually find their place within the family situation. At times, a hint of sarcasm fills the speaker’s depictions: “This can’t be a wonderful scene: / the navy leather passenger seat / & my feelings sprawled all over.” However, a more serious tone develops as the speaker recognizes “I was born a drury daughter.” This image juxtaposes the speaker’s initial recognition of being born a “weary son.” The phrase “weary son” bookends the poem, but in the final lines, instead of relying on the verb “was,” the final statement relies on “can’t”–”I can’t be born a weary son.” The speaker’s “can’t” seems forced, but it may have also developed from a denial imposed on the speaker by society or the family.

“Notes After Watching the Inauguration” relies on repetition and block stanzas. The repetition and block stanzas reinforce words like “decay” and “time.” As the speaker reflects on the election results and what America is, “white boys blare music, use / MAGA banners as decoration on white walls.” The repetition of the word “white” creates a sense of personal and historical entrapment, and this echoes in the second stanza, where the speaker uses the word “white” three times. The poem is also a reckoning with the historical, capitalistic, and systemic oppressions which inherently sicken and kill marginalized people. These include “white folk,” “state troopers,” “Starbucks,” “Republicans,” and “Democrats.” The poem concludes with the lines “This is not my house. Someone else / must open it.” Thus, the speaker reinforces the idea that the systems in place in American politics are designed to teach those within marginalized communities to hate and destroy themselves. It’s an idea which threads through Brookins’ poems, and in “I Admit It,” the speaker explores social media’s role in this seemingly never ending cycle.

“I Admit It” opens with rather domestic scenes of farting in bed while a partner sleeps. However, it segues into a larger space of self-exploration and social criticism. The speaker starkly confesses, “I’ve done unspeakable things & here I am, / tell you so you can get on with it.” The list of “unspeakable things” includes “I cheated on a test” and cheating on a partner and then badmouthing them. It also includes watching a friend “be berated by homophobes” and doing nothing but walking the friend home. The speaker admits to becoming desensitized to the cycle of systemic violence which threatens marginalized communities: “Most times I care less & less about the action plan / for freedom. You don’t have to comment; / you don’t have to convince the police.” The speaker focuses on society’s demand for compliance, and then they ask a startling question: “Can you resist the urge to kill me?” The question echoes the horrors of erasure and colonization imposed by imperialists, dictators, and autocrats on various groups and cultures throughout history and transforms the speaker’s personal experience into a universal one.

Defiance is a delicious theme in Brookins’ collection, and the collection’s speaker celebrates the role of poetry as a means of shaping and communicating that defiance. “I Can Ride My Bike With No Handlebars” is the quintessential defiance poem. It opens with the confessional line “Every day there is something bothering me, / begging me to be a poem.” The speaker initially identifies everyday commonalities such as “leaf shavings” and “dog hair decorating the dark wood floor.” From this point, the speaker segues into a list of personal acts of defiance against “the gaudiness of men.” They admit they have “muted the trumpets praising” their “eventual demise.” They assert, “I’ve never been a gender. / Only a rhythm.” This defiance transforms into a declaration for survival: “All I want to do is live.” The speaker then attests to poetry’s ability to cause revolutions and spark change:

then you can lead a nation with a microphone

with a microphone

with a microphone.

This theme continues in “Traveling to a New Star.”

“Traveling to a New Star” is an exploration of pain, grief, and their ability to completely reshape an individual’s identity and existence. It bears philosophical anecdotes like “Unlike sorrow, grief gets truer when you feel it.” It also carries gentle reminders about the metamorphic power of love: “Love is passion, and passion leads us to these stars.” The speaker makes a call for transforming one’s personal negative energy into a positive one: “Today I’ll take what I have and turn it into / something beautiful. When pain is the only thing that feels true, / I ride the wave of the moon until it drops me off at a new, speckle- / filled home.” The speaker’s words are a stalwart sentiment, a testimony to perseverance, and the determination to make the world a better place one small act of love and kindness at a time.

The poems in Freedom House are bold calls to action for personal, social, political, and cultural reform. Their philosophies and ideologies act as small platforms for a much needed protest against the hateful rhetoric from America’s right. Provocative and rebellious in the best ways, this collection boldly and straightforwardly celebrates otherness, queerness, and blackness in the face of a nation slowly backsliding into its dangerous, racist past.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post