by Nicole Yurcaba

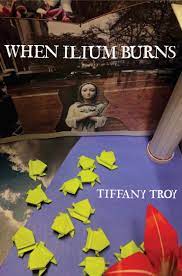

Tiffany Troy’s When Ilium Burns is a bit like a Rubik’s cube: it bears multiple faces, and those faces shift and rotate as one moves through the collection. A first reading might convey an initial interpretation while the second reading on a different day might offer an entirely different one. Working in the collection’s favor is not only this technique, but also its brevity and the careful enjambment prominent throughout the book.

Of course, to understand the collection, one might first need to perform some research. To what does the “Ilium” in the title refer? Is it that broad bone forming the upper part of each half of the pelvis? A misspelling of “ileum,” which refers to the small intestine’s third portion? Or is it the chief city of the Trojan people? If readers guessed the last, good on them. In the Aeneid, “Ilium” is the chief city of the Trojan people. It occupied a key position on trade routes between Europe and Asia. Today, Ilium is known as Troy. As readers progress through When Ilium Burns, they realize this allusion is not an overt one, but an understanding of, or at least a willingness to research, the Greek myths will benefit them. Place, as they will notice, is an imperative theme in Troy’s collection.

“Before the Sea Stirs” consists of four stanzas and 16 lines. Its standout references include a brief mention of Corona Meadow Park, commonly known as Flushing Meadows–Corona Park. The reference to a modern place balances the allusions which follow, specifically the references to Scylla and Charybdis. Do those names sound unfamiliar? If so, one may not be familiar with two quite impressive Greek mythological figures. Both Scylla and Charybdis, irresistible and immortal, guarded the strait, later localized by scholars as the Strait of Messina, through which Odysseus passed. Thus, one might interpret the poem as “the calm before the storm,” since the speaker conveys a peaceful, contemplative scene in which they are walking, contemplating their place and purpose. Besides its allusions to two very impressive Greek sea monsters, the poem also sports impressive words like “chiaroscuro,” which means “an effect of contrasted light and shadow created by the light falling unevenly.”

The poem “Little Maria Wants to Take a Nap” embraces the definition of “chiaroscuro.” One must first think about the name Maria, which originates in Latin and means “of the sea,” “bitter,” “beloved,” or “rebellious.” Many cultures also consider “Maria” a variation of the name “Mary.” Other readers might have a different interpretation, considering that “Little Maria” is the name of the tragic character in the 1931 classic horror film Frankenstein. Again, Troy utilizes the four stanza, 16-line structure. The repetition of initial phrases like “stands in the rain,” “stands in the snow,” and “stands in the dark” turn the poem in a wheel-like fashion, creating a cyclical force within the poem. The poem’s final line is the true hallmark: “You must not let him kill the love in your heart.” It’s filled with force and determination unlike any other in the collection.

“This” opens beautifully: “I specialize in disappointing / people I love, coughing / behind closed doors.” Enjambment can be a difficult technique to master, but in this poem, Troy employs it masterfully. Similarly to what the repetition achieves in “Little Maria Wants to Take a Nap,” the enjambment in “This” turns the poem, creates emotional cycles within the stanzas. “This” is confessional without being self-pitying. The penultimate stanza is the poem’s emblem:

The scientists have discovered how bright

the universe is, but under the light panels

I Google, What if I cannot do this

anymore? Strong up, Master texts me,

but I do not know that yet, as I close my eyes.

The question “What if I cannot do this anymore?” centers this stanza, and the centering is the ideal placement, because, perhaps, it is not only the stanza’s central question, but also the poem’s.

“The Hike” concludes When Ilium Burns. With its utilization of the natural imagery, it resonates with the poems in Stuart Dischell’s The Lookout Man. While many of the poems in Ilium bear a hopeless tone, “The Hike” does not. The third stanza, with its contemplation of the consequences which unfold because of one’s choice, is philosophical:

Who could blame them for forsaking us?

We abandoned our homeland for bigger dreams.

We lost our baby faces and learned to bite our lips

to endure our solitude through the long night.

Hints of longing and the desire to return to one’s origins begin in this stanza, and they permeate the poem’s remaining lines. The speaker reflects:

May we walk back to where the water buffalo roamed

that the golden dog from our childhoods

might save us still from being scattered across

this country, vast as an entire world.

It’s a prayer, an incantation, of desire and return. It’s also a moment in which the speaker is truly comfortable with themself — a new experience for both the speaker and the readers of this collection.

Part bildungsroman, part visceral emotional and physical migration, When Ilium Burns is both personal and cosmological. When Ilium Burns is available from Bottlecap Press.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post