by Izzy Astuto

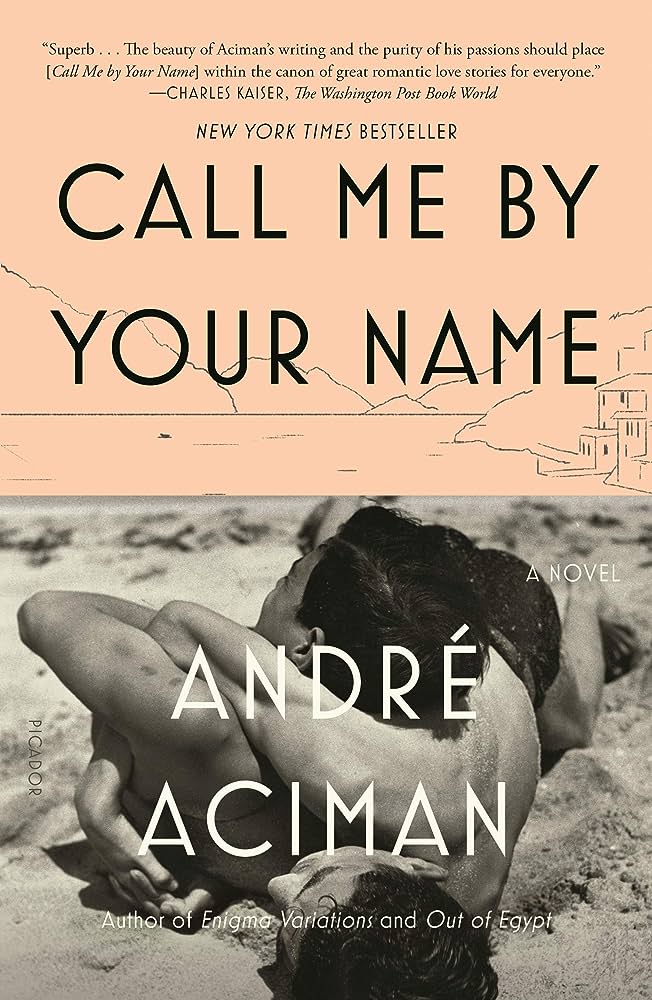

In 2017, the book Call Me By Your Name by André Aciman was made into a movie that received critical success, kick-starting Timothee Chalamet’s acting career and winning Best Adapted Screenplay at the 2018 Oscars. In 2021, rapper and singer Lil Nas X, who became popular with his 2018 hit Old Town Road, released another chart topper referencing the previously mentioned movie called MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name). The key difference between Lil Nas’ music video for his new song and the movie the song’s title took inspiration from is based in the debate between queer assimilation and queer liberation. Queer assimilation is the idea of fitting into a society’s current culture, and becoming “normalized.” Queer liberation, on the other hand, is the idea that current society is corrupt, so why exist within it? For example, the idea of queer liberation is the entire reason that “gay pride” as a concept exists, as it was a way for queer people to distinguish themselves from accepted social and cultural norms.

Many important aspects of queer spaces intentionally go against the grain. For example: drag. Drag is all about taking gendered stereotypes to their extremes or turning them on their head entirely. While one does not have to be queer to do drag, the entire concept was formed around experimenting with gender presentation and sexuality expression and being unapologetic about it, which is all that queer liberation strives for. It operates under the belief that people are born the way they are born, and every person is unique. Just because a key, innate part of a person may upset societal standards does not mean they should have to change just to please society.

Queer liberation is also rooted in anti-capitalist ideals. The essay “Queer Liberation Theory: A Genealogy” by Cameron McKenzie states, “The use of the word ‘queer’ signals a progressive, critical, sex-positive, anti-assimilationist, liberationist perspective as opposed to an assimilationist perspective that strives for respectability, acceptance, prestige, and monetary success on capitalism’s terms.” Capitalism is built on the backs of the poor and discriminated against, and can not operate without someone at the bottom. Many queer people who have had to deal with being on that lower end of capitalism because of factors such as job-based discrimination or health care, (i.e. surgeries and hormones for transgender people being incredibly expensive and not covered by insurance) do not want to simply make things better just for queer people. They do not want anyone to have to experience that poverty, which is why they believe that capitalism, and, by extension, the mere “tolerance” granted to queer people, should be abolished.

So how does this relate to Call Me By Your Name? On the surface, it seems like much of the movie may align with queer liberation’s ideals. After all, it blatantly marketed itself as a gay film, showcasing a clear, distinct relationship between two (presumably) gay men. However, it does this while still painting the relationship as incredibly taboo.

First of all, the main point of debate when discussing this movie is the age gap between the two main characters, Elio and Oliver. Elio is only 17, below the widely socially accepted adulthood age of 18, and Oliver is definitely past that age, at 24. The movie takes place in 1983 Italy, where the age of consent was 14, but this is still an upsetting age gap for many, particularly in the US, because of the maturity difference and power dynamics. Secondly, it is revealed at the end of the movie that Oliver was engaged to a woman the entire time he and Elio were “in a relationship.” This not only taints the relationship because of Oliver’s unfaithfulness, but also maintains the belief that gay relationships are not as valid as straight ones.

While this situation is one that may have happened, it is a very common narrative in queer films. No one is saying that negative situations related to minorities can not be portrayed in movies without giving the community a bad name or perpetuating harmful stereotypes. For example, the 1992 musical Falsettos by William Finn plays with that exact idea. The main character, Marvin, cheats on his wife, Trina, with another man, Whizzer. The rest of the show deals with their divorce and the ups and downs of the relationships between these three characters, along with Marvin and Trina’s son, Trina’s new husband, and two of Marvin’s friends. At the end of the first act Marvin and Whizzer end up breaking up because of the way that Marvin has been treating Whizzer, causing him to also lash out at Trina. The second act picks up two years later once Marvin has been able to work through many of his problems, but in those two years, he has caused a rift between himself and his family because of his actions.

The difference between Falsettos and Call Me By Your Name is the depth in which they go into the character flaws. Falsettos has multiple songs about Marvin struggling with internalized homophobia and toxic masculinity. Meanwhile, Oliver does show reservations at times about his and Elio’s relationship, but the movie never shows why he has these struggles. Obviously insinuations can be made about the time period and such, but since reasoning is not laid out explicitly, one has to wonder why the book and movie had so much time to focus on aesthetics and descriptions rather than unpacking some of the deeper themes the story hints at.

On top of the way in which Call Me By Your Name deals with these issues, another problem stems from the fact that a shocking number of queer movies that make it to the mainstream seem to have some disastrous aspect that subconsciously keeps LGBTQ+ people as victims. That is why even with all of the queer assimilationist problems of Love, Simon, the movie adaptation of the book Simon Vs. The Homosapiens Agenda by Becky Albertalli, so many queer people rejoiced about its popularity and media attention. It was a rom-com for gay people with a happy ending where the main couple got together and actually stayed together, without one of them dying, leaving the other for the opposite sex, or something else of the tragic nature.

Call Me By Your Name also heavily relies on the female gaze. When discussing film, a concept called the male gaze is often brought up, but that is not the only type of fetishization that occurs within movies. The male gaze, according to Oxford Dictionary, is “the perspective of a notionally typical heterosexual man considered as embodied in the audience or intended audience for films and other visual media, characterized by a tendency to objectify or sexualize women.” The female gaze is the same, but for women who are attracted to men. Just like a high school party scene in a movie where two “bi-curious” girls make out in front of gawking, horny jocks, Call Me By Your Name goes out of its way to appeal to females. From the overly aestheticized visuals, which are typically marketed to women, to the casting of the already well-known (and heavily lusted after, primarily by women), Armie Hammer and soon-to-be breakout star and teen heartthrob Timothee Chalamet as the two titular roles, both of whom are not actually gay themselves, the movie almost begged for a female viewer base, which it definitely succeeded in achieving. As much as it tried be an “iconic queer film,” focused on a developing romantic relationship, the romance parts of it feel sexually charged or end up being ruined by the age gap or knowledge of adultery, leaving the sex as the only real indicator of anything beyond friendship. The queer community already has a big problem with being perceived as “sexual deviants” and Call Me By Your Name maintains that idea without questioning it. Karamo Brown of Queer Eye, a licensed psychotherapist and social worker comments about the movie, “I think to myself, ‘If that was an older man, or a perceived college student who looked that much older with a 16 or 17-year-old girl, we would have all had a hissy fit.’ We would have recognized that this is a problem. But for some reason, because it was two men, we’re just like, ‘Oh, well this is just exploration.”

Then we have MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name). Lil Nas X, (also known by his birth name, Montero) began his career with the country, hip hop mashup that is Old Town Road. He built an audience from two of the most notoriously homophobic music genres. As he grew in popularity, he openly came out as gay, including lyrics in his songs that blatantly cemented this fact. While some of that original fanbase left because of this, many of them stayed, using the excuse, “Lil Nas is one of the good ones, because he does not shove his sexuality in your face.” On multiple occasions Montero has spoken out about how uncomfortable this phrase makes him, but those who used it did not seem to care and kept using it.

Then the video for MONTERO came out. Between Montero’s lap dance to the Devil, a male-presenting being in this video, and multiple different drag outfits, a traditionally gay indicator, MONTERO is a slap in the face to that statement. The video also used a lot of religious imagery, specifically Christian. Much of the fan-base he had built up was part of the “religious right,” which includes both white evangelicals and black nationalist Christians, and substantially increased the backlash he received because of this song. Many of the “fans” who just a day ago had been praising him for his subtlety now balked at his “attacks against Christianity.”

This video took the words that Montero claims have been thrown at him over the years from many Christians, in particular that he would go to hell for being gay, and created this video, embracing that concept. Instead of simply accepting the fake tolerance that alienated other queer people, he went out of his way to make people uncomfortable and point out their hypocrisy. He created the perfect microcosm to test out just how easy it is for many of these reactionary conservatives to be baited into anger and hypocrisy.

As mentioned earlier, queer liberation is built on not just liberation for queer people, but other minority groups as well, and Lil Nas’ impact has also done a lot for the Black community. Along with the pedophilic allegations, Karamo Brown has also spoken up about his problems with representation in many mainstream queer films. “I’m tired of this continued narrative of pretty white boys as the only representation of the LGBT community.” In a report called Homophobia, Hypermasculinity, and the Black Church, Elijah Ward writes about the history the black community and church have had with homophobia. “Black churches in the USA constitute a significant source of the homophobia that pervades black communities. This theologically-driven homophobia is reinforced by the anti-homosexual rhetoric of black nationalism.” This has manifested into that lack of intersection that Brown speaks about, wherein often movies with LGBTQ+ people and people of color are not one and the same. With Lil Nas coming out in such an extreme way, he has taken some significant strides for the queer, black community.

The reason Call Me By Your Name and MONTERO are so different is because Call Me By Your Name was created to be eye candy that makes homosexuality more palatable and aesthetically pleasing specifically for those who could and would fetishize it. Lil Nas, on the other hand, has made it clear he will not be toning himself down for anyone’s comfort, pushing his way not only once again to the top of the Billboard charts, but also to the front of the queer community for years to come.

Izzy Astuto (he/they) is a writer currently majoring in Creative Writing at Emerson College. His work has previously been published by Hearth and Coffin, The Gorko Gazette, and Renesme Literary, amongst others. Their Instagram is izzyastuto2.0 and Twitter is adivine_tragedy. More information about him can be found at izzyastuto.weebly.com.

Aciman, A. (2021). Call Me By Your Name. Atlantic.

Ahlgrim, C. (2018, December 13). ‘Queer eye’ star Karamo Brown thinks ‘call me by your name’ is ‘problematic’ because it glorifies ‘predatory behavior’. Retrieved May 19, 2021, from https://www.insider.com/karamo-brown-queer-eye-explains-why-call-me-by-your-name-is-problematic-2018 12#:~:text=Indeed%2C%20the%20story%20takes%20place,been%20the%20case%20in%20Italy.

Call Me By Your Name. Directed by Luca Guadagnino, performances by Armie Hammer and Timothee Chalamet, Frenesy Film Company/La Cinéfacture/RT Features/M.Y.R.A. Entertainment/Water’s End Productions, 2017.

Elijah G. Ward. “Homophobia, Hypermasculinity and the US Black Church.” Culture, Health & Sexuality, vol. 7, no. 5, 2005, pp. 493–504. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4005477. Accessed 19 May 2021.

Falsettos. By William Finn, directed by James Lapine, BroadwayHD, Walter Kerr Theatre, New York City, NY. Performance

Love, Simon. Directed by Greg Berlanti, performances by Nick Robinson, Fox 2000 Pictures/Temple Hill Productions/TSG Entertainment, 2018.

MALE GAZE: Definition of male gaze by Oxford dictionary on LEXICO.COM also meaning of male gaze. (n.d.). Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/male_gaze

McKenzie, C. (2020, November 19). Queer Liberation Theory: A Genealogy. Retrieved May 13, 2021, from https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1193

“MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name).” Youtube, uploaded by Lil Nas X, 24 March 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MdTN0k1i14E

Image Credit: ELENA NICOLAOU

Add your first comment to this post